November 8: The Confluence Region: Rivers Run Through

For millennia, the Confluence Region of North America, where the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi Rivers and their tributaries meet, was a very attractive area for Indigenous settlement, fishing, and hunting. Rivers, creeks, and other streams attracted not just wildlife but provided water for drinking and cleaning, while the forests that once covered the eastern half of the state provided raw materials and fuel for cooking. The caves within the forests and along the streams provided ready shelter for hunter and hunted alike, and tools were made from stone, bone, and wood.

Archaeologists estimate the first human hunters in Missouri to date around 9500 BCE, drawn here by woolly mammoth and giant sloths as prey. Hunter-gathering societies are believed to have begun developing around 7,000 BCE, inaugurating what is known as the Archaic period that lasted until about 1,000 BCE. At about that time, pottery may have begun to be manufactured, inaugurating what is known as the Early Woodland period, with evidence of religious rites around burial being developed. From 5500 BCE to about 400 CE, the Middle Woodland period is characterized by the development of settlements, the domestication of plants such as corn and the development of trade, which especially flourished in eastern Missouri and southern Illinois, thanks once again to travel made easier by river. From Illinois and Missouri to the north, to Louisiana and Mississippi to the south, the Mississippi River began to support a vast trading culture centered more to the east along the Ohio known as Hopewell.

Educational sites of interest related to the earliest human presence within the boundaries of the Diocese of Missouri include Mastodon State Park in Imperial, Rodgers Shelter Archaeological Site in Benton County, the Cuiver River Complex near Troy, and Native American Petroglyphs in De Soto.

November 9: Cahokia and Mississippian Culture

From about 800 CE to 1600 CE, the banks of the Mississippi River near St. Louis were home to a flourishing great civilization known as Mississippian, which stretched from the Southeast as far as Georgia to the Midwest. The explosion in village population was literally nourished by the mixed cultivation of corn, beans, and squash known as “three-sister” agriculture, augmented by abundant game in the forests and rivers which anchored individual settlements. Food production at one point may have supported as many as 40,000 people around Cahokia alone, with their ability to support specialized trades, artisans, and religious leadership peaking around1100 CE. Satellite towns usually covered around 10 square acres, surrounded by wooden pickets. Thanks to a moderate climate, the people who lived here lived outdoors, only sleeping in their wood framed, cane-mat covered houses in winter.

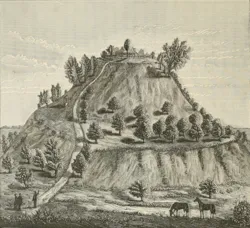

Religion and social hierarchies structured daily life once the fear of want receded. The great towns centered around ceremonial mounds that could reach 100 feet high, and thus the other name for the Mississippian culture is “Moundbuilders.” Large mounds were the location of homes for the elite ruling and religious classes. Smaller mounds were usually burial sites for more common folk. There is much speculation as to what caused the decline of Cahokia: diseases racing ahead of European settlers, carried by trade? Too much agricultural development creating erosion? No one is certain. But by the time Europeans really began making their homes here, Cahokia was largely abandoned and its culture scattered.

At one time, the greatest Moundbuilder settlement covered both sides of the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis to Cahokia in Illinois, along the New Madrid fault. To this day, one of the nicknames for St. Louis is “Mound City” due to the prevalence of ceremonial mounds (estimated to be at least 40 in all) when the French arrived in the late 17th century. The main complex of mounds in the city of St. Louis is now the Convention center complex. Some of the mounds within Forest Park’s boundaries were finally leveled for the 1904 World’s Fair. The only partial mound that still remains on the west side of the Mississippi is Sugar Loaf Mound, located in south St. Louis city in the Dutchtown area north and east of Carondelet. Ironically, the mound has been saved from further destruction by the Osage Nation, which purchased the mound in 2009.

Educational sites of interest related to the Mississippian period in the Diocese include, of course, Cahokia Mounds in Illinois and the New Madrid Historical Museum in New Madrid.

November 10: The Osage: The People of the Middle Waters

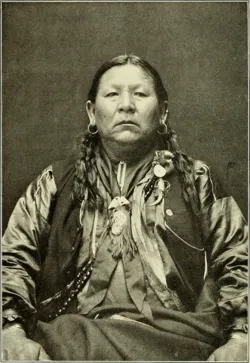

The Wazhazhe People call themselves “The Children of the Middle Waters.” French trappers and traders who encountered them mispronounced that as “Osage.” Their language is Siouan, related to the Kaw (Kansa), Omaha, Ponca, and Quapaw who probably originated near the Ohio River but had migrated to the mouth of the Ohio by 500 CE. The forerunners of the Osage settled near Cahokia for a time, but by the time of its decline around 1350 they moved west along the Missouri River. By the late 17th and throughout the 18th centuries, aided by the arrival of horses descended from those brought by the Spanish from Europe, the Osage had moved to the eastern half of the Great Plains, from Missouri and Arkansas to Nebraska and Kansas.

Osage village life was patriarchal, divided among two main divisions, 24 clans, and numerous more sub-clans. The men headed west to hunt bison on horseback, as well as other game, from March to May, and also from July through August. In between the women planted, and then tended and harvested crops.

European Americans who encountered them remarked on the tall stature and physical strength. The Osage became sought-after allies by the rival European powers invading North America in the 18th century. In 1723 the French established Fort Orleans among the Osage near Brunswick, Charlton County, just to the west of our current diocesan boundaries, and about 125 miles due west of Calvary parish in Louisiana, the first European fort west of the Mississippi.

The resulting proximity to Europeans not only caused exposure to disease but also caused enormous competition among tribal groups to gain trade goods, especially guns. This simultaneously increased inter-tribal warfare and made it far more deadly as European settlement compressed dozens of tribes into ever smaller areas seeking game pelts to trade.

The Louisiana Purchase and subsequent encounters with the Corps of Discovery also marked the Osage’s first treaty giving up land to the Americans in 1808. When William Clark was territorial governor in 1814, he negotiated what ended up being a partial Osage removal to Kansas and now-Oklahoma. More treaties followed in 1818, and in 1824 after Missouri statehood, yet some Osage remained within state boundaries, often to hunt. Finally, in 1837, 500 Missouri militiamen expelled the remaining Shawnee, Delaware, and Osage from Missouri in the so-called “Osage War.”

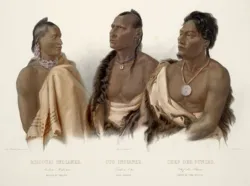

November 11: The Otoe and Missouria

In 1673, Pere Jacques Marquette and adventurer Louis Jolliet met a tribe of indigenous Siouan people who called themselves the Niutachi, numbering perhaps 10,000 people, and alongside the Osage dominated what would become Missouri. When they asked their Peoria guides the names of this people, the guides supposedly replied “Wehmehsoori,” or “the people of the wooden canoes.” The Frenchmen wrote the name “Ouemessourit” on the map, and then put it on the river where they lived too, which later was applied to the entire state.

Like the Osage, it is believed that the Missouri had once dwelled between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River with their kinsmen the Otoe, the Iowa, and the Ho-Chunks. On the movement west, the groups splintered, and the Otoe and Iowa ended up heading north toward Iowa, while the Missouri ventured slightly further toward the Missouri River itself, not far t the west of Kirksville. As they gained access to horses and guns, hunting and warfare became simultaneously more potentially successful and more deadly. For a while, they were second only to the Osage in the estimation of the Europeans. However, over the 18th century, their numbers eroded to around 1,000 due to disease when disaster struck in 1798: their longtime enemies, the Sauk and Fox tribes, ambushed a main body of the Missouria and slaughtered more than half of them. The remnants struggled to live among the Kaw, Osage, and Otoe. Smallpox broke out among them in 1805—just in time to meet the Corps of Discovery under Lewis and Clark.

The 400 or so survivors then affiliated with their kin, the Otoe people, who had once lived along the northern border of our diocese. Together, the combined Otoe and Missouri were confined to the Blue River reservation in Nebraska in 1855, a place of abject misery. In 1881 the Otoe-Missouri were removed again to a small reserve in now-Oklahoma, just across the Arkansas River from where the Osage bought their reservation. But the Missouri name lives on in the name of the river, the state—and two Episcopal dioceses.

November 12: The Iowa

The Iowa, who call themselves Bah Kho-Je (People of the Grey Snow) were, as mentioned previously, once probably affiliated with the Ho-Chunk people originally living near the Great Lakes. Their name’s meaning probably refers to the face that the smoke from their fires turned the snow covering their homes grey. And once again, the French completely changed their name. Ironic that now it is hometown St. Louisans who mispronounce the area’s French names regularly, restoring a bit of balance to the universe.

For much of the time of recorded Iowa history, they lived within or close to the modern boundaries of the state of Iowa concentrated along the Des Moines River, at one point claiming parts of Illinois, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. Their lands claims included the northwestern edge of the Diocese near Kirksville. Between 1824 and 1836, they too were forced to give up their lands to growing white settlement and reduced to a reservation on a narrow strip of land 10 miles wide and 20 miles long straddling the extreme eastern border between Kansas and Nebraska right next to Missouri. In 1883, the tribe split over conditions on the reservation. A separate reservation was created in now-Oklahoma near their old friends the Sauk and Fox. Those who remained in Kansas and Nebraska eventually became successful farmers. The Iowa of Oklahoma, however, were persuade accept the breaking up of their Oklahoma lands into individual allotments; their remaining land was opened to white settlement in a land run in 1890.

November 13: St. Regis Seminary, Florissant (1824-1831): Forced Assimilation

In 1824, Bishop of Louisiana William DuBourg established the second Roman Catholic boarding school for Native children in Florissant off what is Howdershell Road on the same land as St. Stanislaus Seminary. This boarding school operated by the Society of Jesus from 1824-1831, and was subsidized by an appropriation from the so-called “Civilization Fund Act” administered by the newly established Bureau of Indian Affairs within the US government. This subsidy was the first federal money for a Catholic “Indian school” west of the Mississippi River.

Its first five students were two Sauk boys and three Iowa boys ranging in age from approximately six to eleven. A sister school for Native girls was briefly operated from 1825-1831 by St. Rose Philippine Duchesne. Founded under the promise of educating these children, the experience there unfortunately was one of strict religious indoctrination, lack of food and other supplies, and beatings (including flaying with whips on bare backs) for misbehavior. Although originally benevolent in intent by the standards of the time, the purpose was to “civilize” the children and strip them of their culture, language, and traditions. Moreover, classroom instruction other than catechism was soon de-emphasized in order to have the boys do manual labor on the farm attached to the seminary, which was also supported by the labor of enslaved persons owned by the Jesuits. The Jesuits are now engaged in researching and acknowledging regret for their role in operating Indian boarding schools.

The Episcopal Church itself also supported at least eight day and boarding schools for Indigenous children in the United States. At the 80th General Convention held in Baltimore this summer, the Episcopal Church passed Resolution A127, committing resources to researching the history of the Episcopal Church in its support of boarding schools similar to St. Regis Seminary, and to acknowledge and “invest in (Indigenous) community-based spiritual healing centers that will work to address the effect of intergenerational trauma” caused by the subjection of native children to boarding schools, and to engage in education, truth-telling , and reconciliation over the Church’s complicity in supporting these institutions.

November 14: The Trail of Tears in Missouri

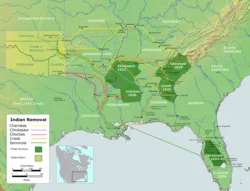

In 1830, after decades of pressure from Southern states, and at the urging of President Andrew Jackson, who had risen to power in part as an “Indian fighter,” the US Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the chief executive the power to exchange lands beyond the Mississippi River for tribal lands held east of the river. Even though the law did not authorize the use of force, tribal resistance from the majority of the “Five Tribes”—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole and Choctaw—led to only fragmentary removal between 1835 and 1838. They rightly pointed out that trading cultivated land with amenities for a wilderness toehold far removed from their traditional homeland was unpalatable.

Then gold was allegedly found on Cherokee land in Georgia, and state and federal officials claimed they could no longer force squatters to respect Native sovereignty. Georgia attempted to enforce laws over Cherokee territory. The Supreme Court upheld the Cherokee Nation’s objection, but President Jackson refused to enforce the decision. The pressure was on. A fraudulent treaty was signed by a fragment of the Cherokee and swiftly ratified, the US Army was sent in to round up resisters to march them westward, in chains if necessary. Those whom they did capture were forced to travel over routes that had already been emptied of supplies by previous waves of emigres. Furthermore, the departure date of November meant the detainees would be traveling through autumn rains and winter cold. Illness and disease caused thousands of deaths.

Three of the routes taken by the Cherokee during the winter of 1838-1839 traversed through land that is now in the Diocese of Missouri. The Trail crossed the Mississippi near Cape Girardeau, and diverged at Jackson. The “Northern” route headed through Farmington toward St. James and Rolla, and then roughly followed the path of what we know as Route 66. The “Hildebrand” route approaches Ironton went nearly due west before reuniting with the Northern route near Marshfield. The Benge route veers south toward Arkansas and passes just a few miles to the west of Poplar Bluff.