November 15: Maria Tallchief (Ki He Kah Stah), Osage: Barrier-defying Ballerina and teacher

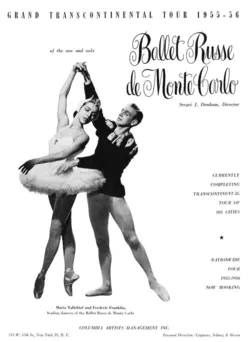

Elizabeth Marie Tall Chief (Ki He Kah Stah) was born in Fairfax, Oklahoma, on the Osage Reservation, in 1925. Both she and her sister Marjorie displayed an early talent for dance, and received lessons thanks to her father’s wealth from petroleum royalties. After her family moved to Los Angeles to expand her opportunities when she was 8, Ms. Tallchief moved to New York after graduating high school. She joined Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo as an understudy, and then received positive reviews for her first performance in 1942. She was the first American to dance with the Paris Opera Ballet in 1947, as well as the first American to dance at the Bolshoi Theatre in 1960.

Despite pressure to “Russianize” her name for fear that contempt for Native Americans would derail her career, she embodied both artistic excellence and pride in her heritage. After dancing as Betty Marie Tallchief in Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo, she accepted de Mille’s suggestion to use “Maria Tallchief” as her stage name. Her sister, a star ballerina in Europe, also adopted the single-word last name. In 1946, she married famed choreographer George Ballanchine. Her signature roles were of the Firebird, which Ballanchine created for her, and the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker. Ms. Tallchief also appeared in the 1952 film “Million Dollar Mermaid” as Anna Pavolova. After retirement from dancing, she opened the Chicago City Ballet school attached to Chicago’s Lyric Opera with her sister, and became an esteemed teacher.

Although one of five remarkable ballerinas of Native ancestry in the mid-20th century, along with her sister Marjorie as well as Yvonne Chouteau (Shawnee), Rosella Hightower (Choctaw Nation), Moscelyne Larkin (Peoria/Eastern Shawnee), she was acclaimed as one of the most brilliant ballerinas of the 20th century. She received the Kennedy Center Honors in 1996. She was also the mother of poet Elise Paschen. She passed away in 2013 at age 88.

November 16: Joy Harjo, Muscogee (Creek) Nation: Artist, Poet Laureate of the United States, and musician

Born Joy Foster in Tulsa, Oklahoma in 1951, this award winning poet and acclaimed musician changed her name to Harjo to honor her Muscogee grandmother’s family name. Joy Harjo recently completed three terms as the 23rd poet laureate of the United States. She also has Cherokee heritage through her mother. After overcoming childhood abuse from her father and stepfather, she first expressed herself through painting, and attended the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe while a teenager. She also played saxophone and sang in an all-Native rock band while there; she played saxophone and flute as well as singing and performing spoken word pieces with a band named Poetic Justice, as well as her current band called Arrow Dynamics.

She has taught at the University of New Mexico, University of Illinois campus in Urbana, the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the Institute of American Indian Arts. She has received numerous awards and honors, including the Lilly Prize, the Griffin Poetry Prize, the Wallace Stevens Award, the PEN Literary Award for her memoir, the American Book Award, the William Carlos Williams Award, the Oklahoma Book Award, the lifetime achievement award from the National Art Awards, induction into the National Native Hall of Fame, being declared an “Oklahoma Cultural Treasure.” She currently serves as the first Artist-in-Residence at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, OK. A strong sense of justice, empowerment, history, and musicality informs her writing. Her nine books of Poetry include In Mad Love and War (1990), Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings (2015) and An American Sunrise (2019). Her signature project as US Poet Laureate was Living Nations, Living Words, an introduction to Native poets that includes a published anthology.

Notable poems by Ms. Harjo include “She Had Some Horses,” “Once the World Was Perfect,” “Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings,” “This Morning I Pray for My Enemies,” and “Eagle Poem,” many of which can be found and enjoyed online at the websites for The Poetry Foundation and the American Academy of Poets.

November 17: The Deloria family, Standing Rock/Yankton Sioux: Historians, scholars, activists

The Deloria family are literally a force of nature among Native intellectuals. Philip Deloria is the 2022 president of the Organization of American Historians and the first tenured Native American professor at Harvard University. Two of his books deal with Native identity and stereotypes: Playing Indian addresses non-Native people appropriating Native cultural aspects, while Indians in Unexpected Places addresses the imaginative expectations that only conceive of Native people as living on reservations and shunning current culture.

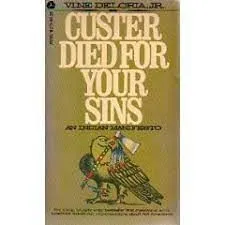

Philip’s father, Vine Deloria, Jr., born into the Yankton Sioux, was a lawyer, theologian, professor of political science, law, and Indian studies and is a noted Native scholar, author, and activist. He was the executive director of the National Congress of American Indians from 1964-1967, and has served as an expert witness in trials regarding Native subjects. His first of his 20 books, the 1969 cultural proclamation Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto, explained the historical and intellectual foundations of the Indian Rights Movement that flourished within and alongside the broader Civil Rights Movement. The library at the National Museum of the American Indian is named in his honor. He died in 2005.

Philip’s uncle, Philip S. “Sam” Deloria, was director of the American Indian Law Center at the University of New Mexico’s law school and an expert of federal Indian policy. Philip’s grandfather, The Rev. Vine Deloria, Sr. (1901-1990), and great-grandfather, The Rev. Philip Joseph Deloria, also known Tipi Sapa, or Black Lodge (1853-1931) were Episcopal priests serving the Lakota people. Philip’s great-aunt, Ella C. Deloria (Angpetu Washte Win, or Beautiful Day Woman), who lived from 1889-1971, was an ethnographer and linguist. She attended Oberlin College and Teachers College, Columbia University, and was an instructor at Haskell Indian Boarding School (now Haskell University) in Lawrence KS, as well as working at the Sioux Indian Museum and the W. H. Over Museum in South Dakota. She was fluent in the Dakota, Lakota, English, and Latin languages, and was the pre-eminent ethnographer of the Sioux people, working on a Lakota dictionary at her passing. Her sister, Susan Deloria, known as Mary Sully (1896-1963), was an abstract and avant-garde artist specializing in triptychs of public figures. Philip has written a book about her works and career.

November 18: Louise Erdrich, Turtle Mountain band of Ojibwe: Novelist, poet, and Pulitzer Prize winner

Karen Louise Erdrich was born in 1954 in Little Falls, Minnesota, but grew up in Wahpeton, Minnesota, where her Chippewa mother and German-American father both taught at what is now Circle of Nations Wahpeton Indian School, then controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. She attended Dartmouth as an undergraduate in the first class to admit women, and earned a master’s degree from Johns Hopkins. Her sister Heid E. Erdrich is also a poet and author.

Most of her novels have dealt with Ojibwe characters and settings. Her first four books centered around the fictional town of Argus, North Dakota, with overlapping characters. Her novel The Round House won the National Book Award in 2012; The Night Watchman inspired by her mother’s father, won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 2020. She has also published the short story collection The Red Convertible and three books of poetry. Her poem, “Indian Boarding School: The Runaways,” from Original Fire: Selected and New Poems is particularly powerful for those interested in the current attempts to reckon with abuses and deaths at boarding schools in the US and Canada.

November 19: Redbone, Yaqui, Yaqui/Shoshone, Southern Cheyenne/Turtle Mountain Chippewa

Redbone was founded by brothers Pat and Lolly Vasquez-Vegas, in 1969 in Los Angeles, with the peak of their career running through 1977. It was the first band of Native Americans to have a top five hit single on the Billboards charts, with the song “Come and Get Your Love, which experienced a resurgence after being prominently featured in the film and soundtrack for Guardians of the Galaxy in 2014. In 1973, their single “We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee” was released but banned from most US radio stations’ playlists due to its political content, although the song charted overseas.

During their peak, all of the members of the band were of Native American and Latino descent; the name “Redbone” is a Cajun term for those of mixed-race ancestry. Bassist/Vocalist Pat and Guitarist/Vocalist Lolly Vasquez-Vegas were of Mexican American and Yaqui-Shoshone ancestry. Lead guitarist Tony Bellamy was of Yaqui ancestry. Drummer Peter (Last Walking Bear) DePoe was of Southern Cheyenne, Turtle Mountain Chippewa, and Rogue River Siletz ancestry. Between 1970 and 1974, Redbone released a series of albums whose songs dealt with Native themes, including Potlatch (1970), Message from a Drum (1972), Already Here (1972), Wovoka (1974), and Beaded Drums Through Turquoise Eyes (1974).

November 20: Jones Benally and family, Dine (Navajo): Hoop dancers, singers, and musicians

Jones Benally is a traditional Dine (Navajo) healer and hoop dancer from Black Mesa, Arizona. His exact age is uncertain, although he is believed to be in his 90s. Jones’s reputation as a healer is so respected that he was employed by the Indian Health Service at their Winslow, Arizona facility to work alongside western- medicine practitioners. Together with his children, Jeneda (born 1974), Klee (born 1975), and Clayson (born 1977), and now grandchildren, he has sung, drummed, and performed internationally, including at the Library of Congress.

Klee, Jeneda, and Clayson also formed the punk rock band Blackfire in 1989. Jeneda and Clayson also perform as a bass and drum duo known as Sihasin (which means “Hope.”). As Jones’s children were growing up, to avoid being sent to boarding school, they moved to Flagstaff, on the border of the Dine reservation, but refused to accept relocation housing. It was there that Jones’ children first personally encountered discrimination for their Native heritage. The mockery they encountered there fueled their performance of punk rock music. They chose the name “Blackfire” after seeing smoke rise from a Peabody Coal Mine in Black Mesa. Clayson has also been an actor. In all their artistic pursuits, however, they try to follow what the Dine people call Hozho, The Beauty Way, expressed in this prayer:

In beauty I walk

With beauty before me I walk

With beauty behind me I walk

With beauty above me I walk

With beauty around me I walk

It has become beauty again

It has become beauty again

It has become beauty again

It has become beauty again

November 21: Linda Hogan, Chickasaw: Poet, teacher, environmentalist, essayist, novelist

Linda Hogan was born Linda K. Henderson in 1947 in Denver, Colorado. Her father was a Chickasaw; her uncle Wesley Henderson helped organize Native Americans who had moved to Denver as part of the federal government’s policy of relocation in the 1950s, and he was an important influence in keeping her connected with her identity as a Native American. She has served on the faculty of the Indian Arts Institute, Colorado College, the University of Oklahoma, and at the University of Colorado, Boulder. She currently serves as Writer in residence for the Chickasaw Nation in Tishomingo, Oklahoma.

Prominent themes in her work across genres include Native spirituality, environmentalism, justice for Native peoples. In 1991 she was both a Guggenheim Fellow and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Literature for her novel Mean Spirit. Her poetry is lyrical, spiritual, compassionate, embracing both the magic and the mournfulness of someone who thinks of herself as a “watcher of the world.” In her poem “The Pine Forest Calls Me,” from her latest book of poetry entitled A History of Kindness (2020), Ms. Hogan writes:

I know prayers rise with smoke

the way some people

are so perfectly uplifted

from their first roots.

But when this life of trying is finally over,

bring to my bed a small branch

smelling of green forest, the melting pure water of snow,

these mysteries discovered

one more time.