November 1: Ousamequin (Massasoit), Wampanoag: Encountering Plymouth

Born in approximately 1590 in what is now Rhode Island, Massasoit was the grand sachem, or leader, of the Wampanoag people, who inhabited the coastal region of what is now New England stretching from Cape Cod to Rhode Island. After the Mayflower, bearing a small band of English Separatist families, arrived in what is now Massachusetts in December of 1620, they settled in the abandoned Wampanoag village of Patuxet, whose residents had been decimated by a plague introduced by European traders who had visited the area in 1616.

Ousamequin established a treaty of mutual aid with the Pilgrims, and maintained friendly relations for nearly 40 years until his death in 1665. With Ousamequin’s assent, Tisquantum (known to European history as Squanto) and other Wampanoags instructed the Pilgrims of “Plimoth Plantation” in techniques of fishing, farming, and cooking that enabled them to survive. Together, the Pilgrims and Wampanoags celebrated the first Thanksgiving in the fall of 1621—due in large part to Wampanoag contributions of five deer to ensure enough food for the gathered peoples. Ironically, the aid rendered in these early years of Pilgrim settlement sowed the seeds of the decimation of the Indigenous inhabitants of the region, which is why it is now observed by many Native peoples as a day of lament.

In the decade following Massasoit’s death, as English immigration accelerated and frayed the relationship between the two peoples, Massasoit’s son Metacom led a confederation of tribes against the Puritan colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, and Connecticut and their own Native allies in “The Great Narragansett War” of 1675-1676. This conflict lasted 14 months and resulted in thousands of Natives dead, hundreds more enslaved, and dozens of villages and fields burned. The English themselves lost 600 soldiers and saw 17 English settlements, including Providence, RI, destroyed.

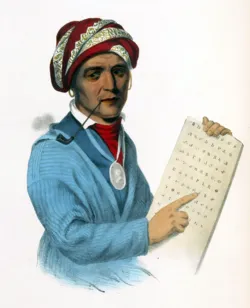

November 2: Sequoyah (George Gist), Cherokee: “Talking Leaves”

Sequoyah was born approximately in 1778, in what is now Tennessee, to a European American father and a Cherokee mother. As a young man, he worked as a trader and a smith. It is believed that around 1809 he began contemplating how to develop a written system for the Cherokee language, recognizing the power such communication gave to European Americans as he watched US soldiers communicating via their “talking leaves.” Despite disapproval by many of his countrymen and the fact that he spoke only Cherokee, he began developing a Cherokee writing system.

Sequoyah’s first attempts at written Cherokee utilized pictograms for every word, but he rejected that as too cumbersome. Eventually, aided by his daughter Ayoka, he broke down the Cherokee language into its unique syllables, realizing there were about 85 in all, he developed a symbol for each syllable, a system known as a syllabary. Although only 6 years old, Ayoka learned the syllabary. However, he and his daughter were charged with witchcraft and placed on trial. After being able to communicate to each other on paper despite being separated, Sequoyah and Ayoka were not only acquitted, but he was asked by some of the judges to teach them how to read and write. He even traveled to the Arkansas Territory, where some Cherokee had removed since the mid-1810s, and taught his system there. In 1825, the Cherokee Nation formally adopted his syllabary, and by late that year the Bible and several hymns had been transcribed in the new writing system.

The system Sequoyah devised was so simple that learners could master it in less than a week; by 1830 the Cherokee achieved one of the highest literacy rates (90%) of any people on Earth. With the assistance of Methodist missionary Samuel Worcester, the Cherokee established their own newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix, in 1828, the first bilingual paper in US history. Sequoyah developed a printed version of his handwritten syllabary to be better suited for use by printing press. He even developed written numerals, although these were rejected by the Cherokee council.

November 3: Sacagawea (Tsi-ki-ka-wi-as), Lemhi Shoshone:

Born in approximately 1788-1790 in modern Idaho among the Lemhi Shoshone, at about age 11, Sacagawea was captured by enemy Hidatsas and sold to an allied Missouri River Mandan village in North Dakota, near present-day Bismarck.

After the Jefferson administration completed the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were hired to lead a Corps of Discovery into this vast new area by traversing up the Missouri River starting at its mouth near present-day St. Charles starting in May, 1804. When winter set in, they camped near the Hidatsa-Mandan village, where French Canadian trapper Touissant Charbonneau, who lived among the villagers, had claimed the teenaged Sacagawea as one of his wives. Charbonneau persuaded Lewis and Clark to hire him as an interpreter, claiming his knowledge of Hidatsa and sign language, and his wife’s knowledge of Shoshone. Sacagawea gave birth to her first child John-Baptiste in February, and in April, 1805, the Corps, now composed of 31 men and one teenaged girl, set out again with Sacagawea’s infant carried on her back. The only other person of color among the Corps was an African American named York, who was enslaved by Clark.

Sacagawea contributed immeasurably to the success of the Corps, interpreting, augmenting their diet with edible plants she foraged, even rescuing critical instruments and supplies during a near-capsizing of one of their boats while her husband panicked. The presence of a woman and child often had the valuable psychological effect of indicating the peaceful intention of the party to new villages they encountered. When the Corps reach Shoshone land, she took charge of interpreting with their leader Cameahwait, to realize that he was her brother. After their emotional reunion, she was able to enlist much-needed Shoshone aid and support for their final push to the Pacific Ocean in November 1805. As the Corps temporarily divided into two parties for the first half of the return journey starting in March, 1806, Sacagawea then helped guide the southern party, led by Clark, back east. When the two groups reunited back in Hidatsa territory, Sacagawea and her husband and son stayed behind. Despite Clark’s praise for her invaluable assistance in his journals, she herself received no pay for her labor on behalf of the Corps. The only other unpaid Corps member was York. Clark later helped raise and educate her son and a daughter, Lisette, in St. Louis. Sacagawea died, probably of typhus, at about age 25.

In 2000, Sacagawea was the first historical woman as well as first Indigenous person (alongside her son) to appear on modern US currency. Sculptor Glenna Goodacre, who also created the sculpture for the Vietnam Women’s Memorial, used a Shoshone student named Randy'L He-dow Teton to depict Sacagawea.

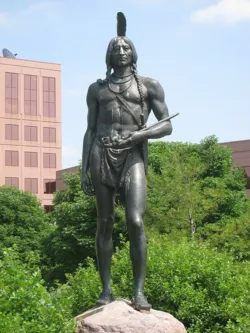

November 4: Tecumseh, Shawnee/Muscogee: Orator and Unifier

On March 9, 1768, as a meteor blazed across the sign in a portent of greatness, Tecumseh, whose name means “Shooting Star,” was born in Piqua village near modern Xenia, Ohio. His father was Shawnee and his mother Muscogee (Creek). His father was killed by white in 1774, and soon after his mother left him in the care of his elder sister Tecumapease and elder brother Cheesekau as she traveled with part of the tribe to Missouri. He was later adopted by Chief Blackfish, and fought alongside him on behalf of the British in the American Revolution.

Within the first 20 years of his life, Tecumseh witnessed three transfers of claimed sovereignty over his homeland, from France to Britain to the US after the Revolution concluded in 1786, and white settlement—and attacks—exploded.

Tecumseh was living in Indiana with his younger brother Tenskwatawa, henceforth known as “the Prophet,” when that brother had a vision of restoring Native power through purging all white customs and influence and uniting in a pan-Indian confederacy stretching from Canada to Mexico. Between 1808 and 1812, Tecumseh travelled as far west as the Ozarks, north to New York, and south to Alabama attempting to persuade tribes to join him. Aided fortuitously by a comet and later the New Madrid earthquake in 1811, some tribes were persuaded.

When the War of 1812 began, Tecumseh travelled to Canada and allied with the British, who promised that if the Natives under his command helped the British win, the Old Northwest Territory would become a separate Indian nation protected by Britain. Despite capturing Detroit and fomenting a Muscogee uprising in Alabama, he and his British allies failed in an invasion of Ohio, and Tecumseh was killed after retreating into southern Ontario at the Battle of the Thames River in October 1813. He was buried secretly, and his body never found. But with his death, the last great wave of Indian resistance in the lower Midwest and South disintegrated, and US government insistence on clearing the lands east of the Mississippi River of native inhabitants intensified with little hope of resistance.

November 5: Wilma Mankiller (A-ji-luhsgi), Cherokee: Activist, Chief, Humanitarian

Wilma Pearl Mankiller was born near Tahlequah, Oklahoma, on November 18, 1945, one of eleven children raised on a farm named Mankiller Flats which had been granted to her grandfather as part of compensation for resettlement. After the farm failed when she was 10, she and her family moved to a poor neighborhood in San Francisco as part of the US government’s relocation policy that attempted to disperse tribal communities and terminate tribal governments starting in 1956. From a young age, she engaged in activism to preserve Native culture and identity, joining the newly organized Native American Rights movement.

In 1969, Ms. Mankiller participated in the American Indian occupation of the abandoned Alcatraz Island, based on ignored treaty language that returned any abandoned military forts to Native ownership. Educated as a social worker, she became director of the Native American Youth Center in Oakland and also helped the Pit River Tribe as it fought a seizure of its lands by Pacific Gas and Electric. In 1977, she moved with her two daughters back to Oklahoma to try to reclaim her family’s farm. After struggling to find work, she was eventually hired as economic stimulus coordinator for the Cherokee Nation, and founded their Community Development Department, working to build a sense of empowerment in impoverished communities that often struggled with high unemployment and a lack of infrastructure and basic services.

In 1983, Ms. Mankiller was elected deputy principal chief of the Cherokee Nation. In 1985, she became principal chief when her predecessor was appointed head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, becoming the first woman to lead a major Native American nation. During her tenure, she nearly tripled tribal enrollment; raised standards for education, health care, and housing; increased employment opportunities; and worked to reduce infant mortality. She was reelected in 1987 and 1991, serving a total of 10 years, only stepping down in 1995 due to poor health. Her honors included being named Ms. magazine’s woman of the year in 1987, induction into the National Women's Hall of Fame in 1993, and receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Clinton in 1998. In retirement, she served as an advocate and speaker for social justice and Native and women’s empowerment.

Ms. Mankiller passed away in April of 2010 after a valiant struggle against pancreatic cancer.

November 6: Esther Ross, Stillaguamish: Demanding Recognition

Photo courtesy of the Stillagamish Tribe of Indians, used by permission.

Esther Ross was born in 1904 in Oakland CA, the daughter of a Norwegian American father and a Stillaguamish mother. The Stillaguamish traditionally lived along the Stillaguamish River largely in Snohomish County, Washington. In 1855 the US government gathered the leaders of more than 22 tribes around Puget Sound, including Suquamish leader Chief Seattle, and concluded a treaty with them in which they relinquished the lands they traditionally claimed in the area in exchange for four reservations and fishing rights. Promises were also made orally to the tribes prior to signing by Washington Territory Governor Isaac Stevens. Several of the tribes who signed the treaty believed that they would be given their own reservations, including the Stillaguamish. When they learned that they would instead be required to live on a reservation with the Tulalip people, many of the Stillaguamish refused to leave their homeland, even though no longer theirs. Over the generations their population, never above more than a few hundred at best, declined.

In 1926, and by that time married and with a small infant, Esther Ross was contacted by relatives in Washington state to come and help her people file federal claims for the US government’s unfulfilled promises. Mrs. Ross learned that the federal government conveniently refused to officially recognize tribes who lacked land, as the Stillaguamish did. This meant that the 66 remaining officially enrolled members were ineligible for any of the benefits that had been delivered to larger tribes under the Point Elliot Treaty. For over 50 years Mrs. Ross became notorious for constantly calling upon government officials and loudly demanding to be heard, to the point that officials were known to hide when they heard that she was in the building.

In 1976, celebrations of the US bicentennial included a highly publicized wagon train that traveled across the continent-- and near the souvenir store that served as the Stillaguamish meeting place and center of operations. Mrs. Ross announced that the tribe would attract attack the convoy around the wagon train unless they were granted official recognition by the Department of the Interior, landless or not, noting that they had fought for their rights for nearly 50 years, and that at 70 years old she was done waiting. The story soon made international newspapers across the world and proved highly embarrassing to the US government.

On the day the wagon train was scheduled to arrive near the Stillaguamish’s traditional homeland, the secretary of the interior sent a special assistant by plane to meet Esther Ross. He promised official recognition within 30 days, but had brought no documentation, and Esther Ross knew that she and her people had been lied to repeatedly before. When the wagon train actually arrived, it was greeted by approximately 200 people blocking the road. Esther's son Frank stopped the lead horse and informed the wagon master that they weren't moving. Esther then appeared after several moments and described the wagon train as symbolizing a trail of broken promises and destructed lives for Native peoples. She then symbolically handed the wagon master a letter for the secretary of the interior and a good luck medal and allowed him to continue. And yet still the Stillaguamish remained unrecognized. Finally, in October of 1976, the federal government officially recognized the tribal government and claims of the Stillaguamish, despite being one of the smallest tribes of indigenous people in America, and a few weeks later she was named Chairman for her indefatigable work for her people.

November 7: Debra Haaland, Kawaik People (Laguna Pueblo), Secretary of the Interior

Debra Anne (Deb) Haaland was born on December 2, 1960, to a Laguna Pueblo mother and a Norwegian-American father. Although born in Winslow, Arizona, she calls herself a “35th-generation New Mexican” due to the presence of the Pueblo people on these lands dating back to at least the 12th century. Both her parents served in the military, with her father’s military career moving the family frequently until they moved to Albuquerque to be near family who lived in Mesita village in the Pueblo of Laguna 45 miles to the west in the San Mateo mountains near the Continental Divide. As a young adult she attended the University of New Mexico and earned a BA in English. She gave birth to her daughter Somah immediately after graduating and started her own business to support them, struggling to avoid homelessness as well as seeking—and being denied-- SNAP benefits.

Ms. Haaland nonetheless completed law school in 2004 at the University of New Mexico, specializing in Indian law. She later served as the first female chairwoman of the Laguna Development corporation while serving as tribal administrator for the San Felipe Pueblo from 2013-2015. In 2018, she was one of two Indigenous women who became the first Native women elected to the House of Representatives, along with Sharice Davids of the Ho-Chunk Nation in Kansas. Her focus as a Congresswoman was missing and murdered Indigenous women, climate and environmental justice as well as pro-family policies. In 2021, Rep. Haaland was nominated by President Biden to serve as the first Indigenous secretary of the Interior, which oversees the Bureau of Indian Affairs. As Interior Secretary, Ms. Haaland has created a new “Missing and Murdered Unit” within the Bureau of Indian Affairs to investigate the disproportionately monumental numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women and created the Federal Boarding Schools Initiative to investigate generations of Native children suffering abuse, neglect, and death at boarding schools funded through the 1819 Civilization Fund Act.